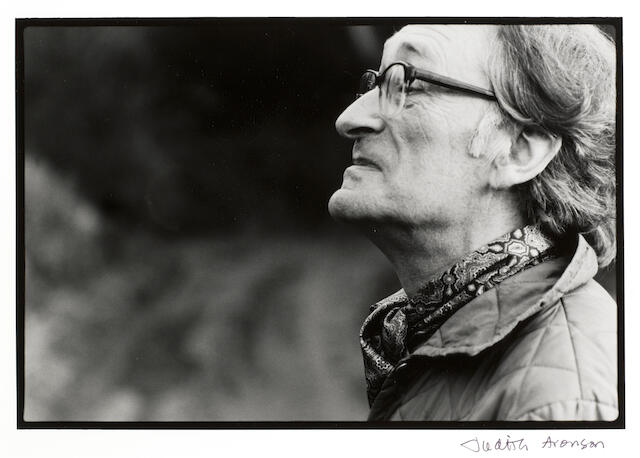

Willard Spiegal in the Paris Review (Winter 1998)

TOMLINSON interviewed

As I mentioned, my sense of America cohered out of many fragments, among them that tiny reproduction of a Georgia O'Keeffe, utterly unknown here at the time. I came to America at a period when the New York School had shifted attention from Paris to that city. For me, it was one of those periods of rapid assimilation—Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, particularly Gorky. But then I wanted to know more about what came before and gradually, or rather in quick leaps during the years, I managed to acquaint myself with the whole long story, going back to the Hudson River landscapes of Frederic Church and other nineteenth-century painters. I became a friend of the great collector Seymour Adelman, largely because he heard me read a poem on Thomas Eakins. He came up to me after the reading and said: “Would you like to see some of Eakins's photographs?” Ask and it shall be given! I asked a Sante Fe friend of Georgia O'Keeffe how I could get to see so reclusive a person. That, too, was arranged, and one morning—we were living in Albuquerque at the time—a telegram arrived from Abiquiu with an invitation to lunch. When I wrote up the visit many years later and it appeared in The Hudson Review— O'Keeffe was in her nineties by this time—another telegram and another invitation. She'd actually read the article. So America meant places and art, and it also meant people.

TOMLINSON

I was embodying Donald Davie's description of syntax as “articulate energy”—and underscoring it with rhyme and half-rhyme. There is the clarity and constancy of a four-beat line that also records motion and change, and rhyme plays its unexpected part in the reconciliation (frequently to be canceled) of those opposites. But the underlying factor is that of a fluid but lucid line that continually encounters things and then moves on. What keeps the experience alive is an unclotted diction. The great lesson came from eighteenth-century verse with its verve and clarity—from that and also from the Americans. Not so much Stevens here as Moore and the Pound of “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley.” But the line is what matters: it must be supple and it must be lucid. It can be as slim as you like (another lesson from American poetry) or it can marshal many unstressed syllables around its four-stress base. I feel the typical movement of these poems reenacts the way we perceive things—reason and feeling trained on a world that is other than we are.

TOMLINSON

I was embodying Donald Davie's description of syntax as “articulate energy”—and underscoring it with rhyme and half-rhyme. There is the clarity and constancy of a four-beat line that also records motion and change, and rhyme plays its unexpected part in the reconciliation (frequently to be canceled) of those opposites. But the underlying factor is that of a fluid but lucid line that continually encounters things and then moves on. What keeps the experience alive is an unclotted diction. The great lesson came from eighteenth-century verse with its verve and clarity—from that and also from the Americans. Not so much Stevens here as Moore and the Pound of “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley.” But the line is what matters: it must be supple and it must be lucid. It can be as slim as you like (another lesson from American poetry) or it can marshal many unstressed syllables around its four-stress base. I feel the typical movement of these poems reenacts the way we perceive things—reason and feeling trained on a world that is other than we are.

TOMLINSON

A short time ago you reminded me that my career had gone on for fifty years. I was about to put you right, but then realized that you were indeed right. It is, unbelievably, fifty years since I began. What do I try to be on my guard against? The fact that I exercised that kind of watchfulness at the beginning, so that now I sit down fairly certain that I cured a lot of bad habits more than half a life ago, in the first phase of that fifty-year period. Blake was the problem and his prophetic books. Blake simply lost the bounding wiry line of his lyrics when he came to write those long lines of the prophecies. Without having experienced the discipline of the bounding line, I flung myself into the shapeless fume of putting the world right by repetition. I was also trying to be a painter at that time and attempted to integrate illustrations and text. The illustrations were the better part. The text was nowhere. I had read Whitman too, and my last school prize (the influence of that German teacher) was Nietzsche's Thus Spake Zarathustra—fatal from the point of view of diction and its encouragement to be hortatory. Since God was dead, I summoned forth the gods—shades of the weaker side of D.H. Lawrence here. The vatic and the hortatory! What could have been worse? I wanted to pull down the cathedrals and consign them to the graveyard of dead giants. (Of course, I didn't really believe all that, but why did I say it?) Occasionally something of the aphoristic side of Blake came through in the shape of the more symmetrical propositions of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.