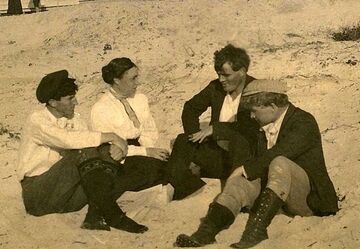

George Sterling, Mary Austin, Jack London,

Jimmy Hooper, Carmel.

THE APOTHECARY'S

TS red and emerald beacons from the night

TS red and emerald beacons from the night- Draw human moths in melancholy flight,

- With beams whose gaudy glories point the way

- To safety or destruction--choose who may!

- Crystal and powder, oils or tincture clear,

- Such the dim sight of man beholds, but here

- Await, indisputable in their pow'r,

- Great Presences, abiding each his hour;

- And for a little price rash man attains

- This council of the perils and the pains--

- This parliament of death, and brotherhood

- Omnipotent for evil and for good.

- Venoms of vision, myrrh of splendid swoons,

- They wait us past the green and scarlet moons.

- Here prisoned rest the tender hands of Peace,

- And there an angel at whose bidding cease

- The clamors of the tortured sense, the strife

- Of nerves confounded in the war of life.

- Within this vial pallid Sleep is caught,

- In that, the sleep eternal. Here are sought

- Such webs as in their agonizing mesh

- Draw back from doom the half-reluctant flesh.

- There beck the traitor joys to him who buys,

- And Death sits panoplied in gorgeous guise.

- The dusts of hell, the dews of heavenly sods,

- Water of Lethe or the wine of gods,

- Purchase who will, but, ere his task begin,

- Beware the service that you set the djinn!

- Each hath his mercy, each his certain law,

- And each his Lord behind the veil of awe;

- But ponder well the ministry you crave,

- Lest he be final master, you the slave.

- Each hath a price, and each a tribute gives

- To him who turns from life and him who lives.

- If so you win from Pain a swift release,

- His face shall haunt you in the house of Peace;

- If so from Pain you scorn an anodyne,

- Peace shall repay you with a draft divine.

- Tho' toil and time be now by them surpast,

- Exact the recompense they take at last--

- These genii of the vials, wreaking still

- Their sorceries on human sense and will.

| "The Apothecary's" is reprinted from The House of Orchids and Other Poems. George Sterling. San Fran |